‘Phone seismometers’ prove their worth

Jonathan Amos / Dec. 17: The researchers behind an app that turns a smartphone into an earthquake detector say they have been thrilled by the take-up and performance of their citizen science network.

Jonathan Amos / Dec. 17: The researchers behind an app that turns a smartphone into an earthquake detector say they have been thrilled by the take-up and performance of their citizen science network.

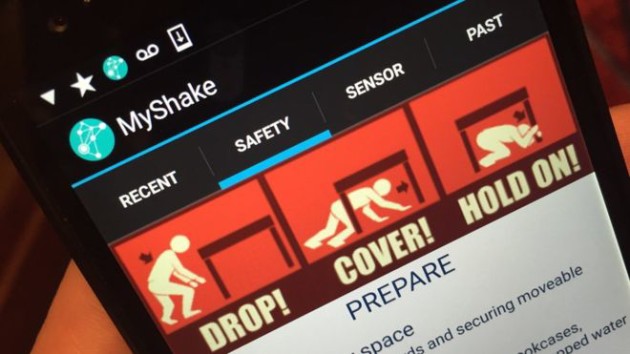

MyShake was launched for Android devices in February and has now been downloaded over 200,000 times. Enabled phones have recorded hundreds of quakes all over the globe since then – some as small as magnitude 2.5. These more sedate tremors were picked up in Oklahoma.

Traditionally, this US state has not been considered earthquake country but seismic activity has increased as a consequence of local oil and gas production.

Prof Richard Allen from the University of California at Berkeley said MyShake had become a useful tool for residents to monitor what was occurring in their region.

“These are induced earthquakes due to wastewater pumping. So there are lots of issues around what might happen, how big these earthquakes might be – and there’s been a lot of pushback.

“We want to empower people to understand what the process is,” he told BBC News.

The MyShake app relies on a sophisticated algorithm to analyse all the different vibrations picked up by a phone’s onboard accelerometer.

This algorithm has been “trained” to distinguish between everyday human motions and those specific to an earthquake.

It works in the background – much like health apps that monitor the fitness activity of the phone user.

Once triggered, MyShake sends a message to a central server over the mobile network. The hub then calculates the location and size of the quake.

“MyShake is performing better than we’d hoped,” said Prof Allen.

“We are actually recoding very small magnitude earthquakes, down to magnitude 2.5 in places like Oklahoma and California. We’re recording the bigger earthquakes – the Ecuador quake in April, M7.8, is the largest so far; and also really deep earthquakes, down to depths of 350km.

“So, from a scientific standpoint, it’s starting to produce this incredible dataset and we’re just beginning to understand what we can do with it.”

He came to announce a new version of the app that now pushes notifications to users.

This is a key next step because the idea eventually is to use the detections being made by devices to issue alerts.

In a dense network, the phones closest to the epicentre would sense the oncoming shaking and then tell cells further afield of the danger heading their way.

The early warning might only amount to a few seconds, but that would at the very least give people the thinking space to start to adopt the famous safety routine – to “drop, cover and hold on”.

The notifications now being issued with the new app version are being served from conventional seismic networks, and they arrive some minutes after the event.

But as more and more phones join the MyShake system and the Berkeley team improves its detection algorithm, the big switch to an early warning mode should be possible.

UC Berkeley developer and graduate student Qingkai Kong reported to the AGU meeting on performance of the app.

He showed how phones could readily detect the first seismic waves to arrive at a user’s position – the so-called P-waves. These less destructive vibrations run ahead of the far stronger and more damaging S-waves.

Being able to distinguish between the two is at the heart of early warning capability.

“We already have the algorithm to detect the earthquakes running on our server, but we have to make sure it is accurate and stable before we can start issuing warnings, which we hope to do in the near future,” said Kong.

The v2 release of MyShake is now available in the Google Play store. An iOS version should be ready for download in springtime. bbc.com