MIT Researchers Identify Cells That Represent Feelings of Isolation

February 18: Humans, like all social animals, have a fundamental need for contact with others. This deeply ingrained instinct helps us to survive; it’s much easier to find food, shelter, and other necessities with a group than alone. Deprived of human contact, most people become lonely and emotionally distressed.

February 18: Humans, like all social animals, have a fundamental need for contact with others. This deeply ingrained instinct helps us to survive; it’s much easier to find food, shelter, and other necessities with a group than alone. Deprived of human contact, most people become lonely and emotionally distressed.

In a study appearing in the February 11 issue of Cell, MIT neuroscientists have identified a brain region that represents these feelings of loneliness. This cluster of cells, located near the back of the brain in an area called the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), is necessary for generating the increased sociability that normally occurs after a period of social isolation, the researchers found in a study of mice.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time anyone has pinned down a loneliness-like state to a cellular substrate. Now we have a starting point for really starting to study this,” says Kay Tye, the Whitehead Career Development Assistant Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, a member of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, and one of the senior authors of the study.

While much research has been done on how the brain seeks out and responds to rewarding social interactions, very little is known about how isolation and loneliness also motivate social behavior.

“There are many studies from human psychology describing how we have this need for social connection, which is particularly strong in people who feel lonely. But our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying that state is pretty slim at the moment. It certainly seems like a useful, adaptive response, but we don’t really know how that’s brought about,” says Gillian Matthews, a postdoc at the Picower Institute and the paper’s lead author.

Only the lonely

Matthews first identified the loneliness neurons somewhat serendipitously, while studying a completely different topic. As a PhD student at Imperial College London, she was investigating how drugs affect the brain, particularly dopamine neurons. She originally planned to study how drug abuse influences the DRN, a brain region that had not been studied very much.

As part of the experiment, each mouse was isolated for 24 hours, and Matthews noticed that in the control mice, which had not received any drugs, there was a strengthening of connections in the DRN following the isolation period.

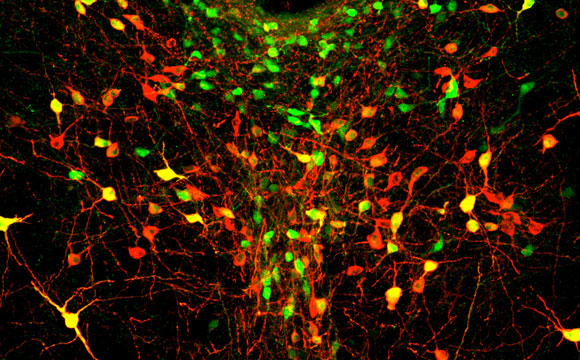

Further studies, both at Imperial College London and then in Tye’s lab at MIT, revealed that these neurons were responding to the state of isolation. When animals are housed together, DRN neurons are not very active. However, during a period of isolation, these neurons become sensitized to social contact and when the animals are reunited with other mice, DRN activity surges. At the same time, the mice become much more sociable than animals that had not been isolated.

When the researchers suppressed DRN neurons using optogenetics, a technique that allows them to control brain activity with light, they found that isolated mice did not show the same rebound in sociability when they were re-introduced to other mice.

Source: Anne Trafton, MIT News